How one Mom rose to head of probation

From the Salinas Californian

Not many women restart their career in their 40s, but Monterey County Chief Probation Officer Marcia Parsons did. And to her, it really wasn’t a big deal.

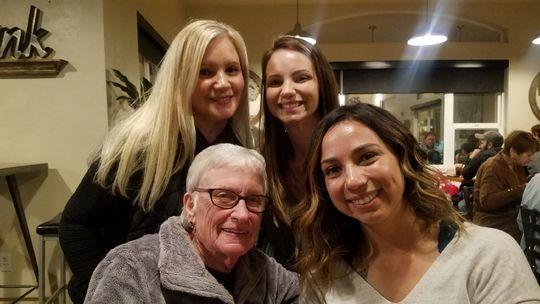

Parsons worked in her early 20s as a probation officer but left to be a stay-at-home mom when she got pregnant with her daughter, Julie Lavorato.

“I was very fortunate to (stay home),” said Parsons. “I knew Julie was probably the only child I was going to have, and I wanted to do that.”

Her daughter gave her a run for her money, though.

Lavorato admits that she wasn’t the easiest child to parent. Although she never was in trouble with the law, by her teens she was regularly truant, preferring instead to do her hair in the bathroom or grab breakfast down the street with friends, rather than go to class. Her experience parenting Lavorato later came in handy for Parsons, once she returned to work.

Parsons divorced her husband when her daughter was 16. While she was a stay-at-home, she also obtained her law degree.

And after two decades out of the workforce, she returned — clerking and substitute teaching special needs students in Salinas.

After a few years, she was offered a full-time position in probation again and snapped it up, becoming the department’s first armed female officer in the early 90s.

“Probation had changed considerably since I left,” Parsons said, likening probation officers in the 1970s to social workers. They carried no handcuffs, no pepper spray, no weapons. The change was a shock to her, Parsons said, but felt it was necessitated by the change in population over time.

“I think being a stay-at-home-mom…taught me a lot about juveniles, and how they don’t always do what you want them to do” Parsons said. “Although Julie never got in trouble, she walked the line.”

It also taught her patience, she said, which is not just helpful, but necessary when dealing with an at-risk youth population.

“It’s about the relationship with the kids,” she concluded.

“She was an amazing mom while I was growing up,” said Lavorato. “I’m very thankful she was there for me. She walked me to school and walked me home. I never felt like anything was different when she went back to work.”

Balancing motherhood and career

Women’s pay and career trajectories tends to stagnate after having children, says research published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the American Economic Review and the Journal of Marriage and Family, among others. Furthermore, movements like the #MeToo movement and surveys have shown many women also experience passive or active gendered harassment in the workplace.

Yet, Parsons said neither impacted her, though she added it may have helped that she returned to work when her daughter was already an adult, no longer dependent on her.

“I never even gave it a thought,” she said. “We worked together, I stood next to them at the range, and took my shots.”

She put her hands together, mimicking a gun, pointed it in the distance and pulled the imaginary trigger, demonstrating.

“I never felt I’d been treated differently,” she said.

Over the next stage of her career, Parsons worked in every department of probation, eager to learn everything she could.

“Anytime there was a chance for a transfer, my hand went up. I wanted to learn something new,” she said. After about 15 years in Probation, Parson was asked to be assistant chief to Manuel Real, later rising to the head of the department after Real’s retirement in 2014.

Parson’s choices and career have always impressed and influenced Lavorato’s decisions, her daughter said.

“I always watched my mom. I always wanted to be just like her. I do try to carry that. There’s nothing about my mom that you don’t see for yourself.

“I think the one thing I learned from my mom is just if I see something I want, I’m going to go out and get it,” Lavorato said. “I don’t expect anyone to hand me anything. I definitely take that with me.”

At 75, her own retirement is the last thing on her mind. Parsons jokes that she already had her retirement, playing tennis during the day while her daughter was at school.

“She always says, ‘The day I don’t love it is the day I’ll retire,’” said Lavorato.

“If I didn’t love it, I wouldn’t still be here,” Parsons said.